The Inlander

Other than its baby-pink door; the modest structure looks like any other industrial shop on Seattle’s Lake Union. Heavy power lines fade into the gray exterior, and shipping trucks pull in and out the narrow driveway. But behind the corrugated metal façade burns one of Seattle’s most flamboyant treasures: the home and studio of the city’s glass king, artist Dale Chihuly.

Chihuly is made of the stuff from which legends come. Dynamic. Opulent. Eccentric. Beginning with only a wooded parcel of land about 20 years ago, he built a glass kingdom across the mountains that now gleams bigger than life. Seattle and its outlying areas are often dubbed the “glass capital of the world.”

The heart of Chihuly’s empire is here, sandwiched between a towering bridge and Ivar’s Restaurant – it is known simply as the Boathouse. Inside and up a narrow stairway, a spacious studio opens to crisscrossed windows that reach from floor to ceiling, revealing a stunning view of the ship canal. Tall, silent boats border the opposite shore. Seagulls ride the restless waves.

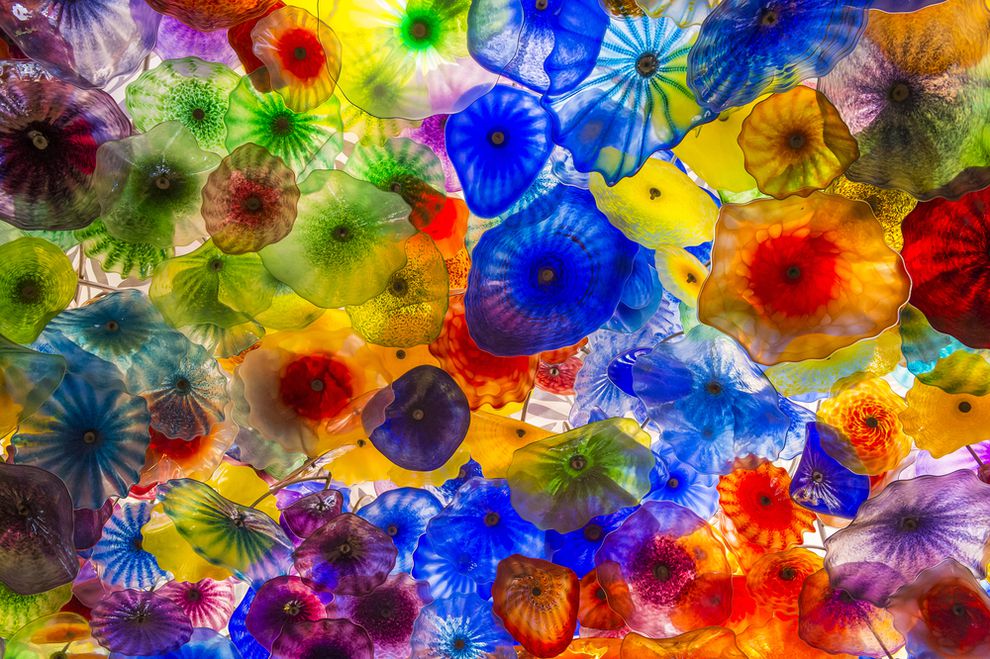

This morning, the Boathouse is quieter than normal. Chihuly, a pudgy man topped with a frizzy mass of brown, corkscrew curls and a pirate-like black eyepatch, is noticeably absent while his staff prepare for one of his legendary parties. They hang enormous paintings, abstract swoops and swirls by Chihuly, and rearrange mountains of glass: giant bubbles of glass in mottled gold and green called Niijima Floats, Machia, spreading vessels with mosaic color patterns, and glass baskets with intricate designs that slump into one another.

Down the hall and around the corner, more glass fills Chihuly’s personal swimming pool. Two of his chandeliers, one a blue Medusa, the other an inverted pyramid of sun-yellow squash, dimly light the room. At the bottom of the pool, lit from the sides, hundreds, if not thousands, of glass pieces, glow like embers. Canary yellow, cobalt blue, orange and hot-pepper red, they catch the light and reflect it in ripples across the walls. Each piece, like all of his work, is carefully photographed and catalogued by the artist.

Some – a few Seattle art critics in particular – bristle at what has been called Chihuly’s “megalomaniacal” nature. They condemn his excess and scoff at his blatant image building. While they make valid points, no one can argue that his glass sculpture is anything but wildly popular, owned by presidents, movie stars and kings.

The inferno where these pieces metamorphose from simple powders to sculpture worth up to half a million dollars is called the “hot shop.” And even with Chihuly racing across the globe, the work goes on. In fact, Chihuly hasn’t blown his own glass since 1976, when a car accident left him blind in one eye, robbing him of the depth perception necessary in glassblowing

Teams led by Chihuly’s gaffers, head glassblowers who work with him closely, create the glass. “It’s intimate,” says Martin Blank, the gaffer at today’s work session. “I have to get into his head, and I can sense whether he’ll like it or not. Our job is to create a palette of work for him. He doesn’t have to be here.”

It’s a step back in history. Artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo DaVinci often worked with assistants to complete their masterpieces, and glassblowing has traditionally been done in team form. Even Louis Comfort Tiffany, which whom Chihuly is often compared, hired glass artists to shape his ideas.

When Chihuly is at the Boathouse, he makes abstract paintings as a kind of pattern for his workers. Working on the deck overlooking the lake, on the studio floor, or in the hot shop itself, he squirts liquid acrylic paint straight out onto the paper, sometimes using two or three bottles at a time. Then he works the paint with his hands, a bristle broom and a long-handled mop, shaping new ideas into bold strokes and vibrant color.

But today,mhot shop workers don’t need a pattern. They’re making something they’ve formed many times before, bright red Persians that resemble giant butterflies with ruffled edges and intricate veins like spider webs.

The hot shop – a room ablaze with fiery ovens and blow torches – is set up in a traditional Italian style with a team of several artists. Today there are eight. Rock and roll music blasts from the speakers as workers dressed in jeans and t-shirts prepare for the first blow. Each has his or her specific part. “It’s like a dance,” says one artist.

A worker brandishes a five-foot-long rod with a small white bubble of glass on its end. Only the center burns gold. The bubble is colored, shaped, heated and added to until it grows to the size of a football. Then it’s carried to Blank, the gaffer, or as one worker calls him, “the team’s opposable thumb.”

Blank, who rushes in late carrying a leather suitcase filled with metal tongs and spatulas that look like barbecue tools, is a young man, with tight, black curls and a cherubic face. He takes the rod and spins it sideways on a sawhorse-type stand. Another worker drips a flow of colored glass on the piece’s surface, creating a spiral of red. The rock and roll music switches to hip-hop.

After another heating, Blank and three other men “blow” the Persian. One worker spins the rod to keep the glass from drooping, and a second squats at its end, blowing through the hollow core to enlarge the form. Simultaneously, Blank shapes the piece, working it with metal tongs and a thick wad of damp newspaper. The fourth man protects Blank’s hands from the heat with heavy wooden paddles.

The team uses the same tools Italian glassblowers used centuries ago, when they were isolated on the island of Murano, about a mile north of Venice. At that time, glassblowing was such a secretive and valued craft that workers were beheaded if caught leaving. Those who escaped to England were knighted.

But today, the secrecy is gone as Bland and his entourage struggle to explain the consistency of the spinning glass. “It starts out like bread dough, but it changes,” says Blank over his shoulder. “It has a skin, kind of like a hot-water bottle.”

The team shapes, colors and transfers the Persian to another rod called a putty for the final heating and the spin-out, the riskiest part of the game. When it comes out of the oven, the piece is at an almost liquid state, around 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Blank spins the rod on a metal frame until the ends of the giant sunburst flare. Then, taking it from the frame, he points the rod toward the floor and continues spinning like a man dancing with a southern belle in a hoop skirt.

As the piece cools, the sides, at least four feet wide, catch and fall, capturing the pulsating rhythm of the hot shop. “You’re walking a tightrope,” says Blank of the spin-out. “You want to go as far as you can without it breaking.”

In the final act, a worker dressed like an astronaut with massive oven mitts enters stage left. Blank turns and drops the finished piece into his arms. Then the room erupts with a shout, “Bravo! We’re off and rolling.”

A full version of this story was published in The Inlander.